Born of Conviction statement 'an atomic bomb': Methodist ministers fought racism in the 1960s

LaReeca Rucker:

The Clarion-Ledger

As a student at Millsaps in the 1970s, Joseph T. Reiff found his heroes in a group of ministers who forged "a crack in the armor of the closed society" that existed in Mississippi in the 1960s.

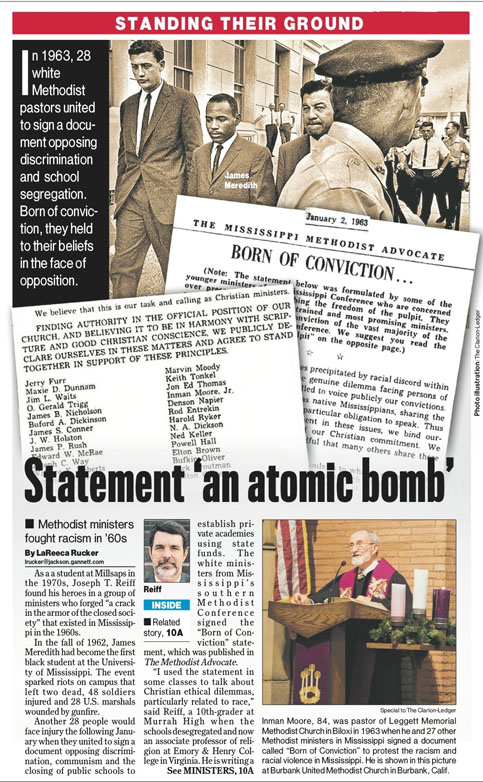

In the fall of 1962, James Meredith had become the first black student at the University of Mississippi. The event sparked riots on campus that left two dead, 48 soldiers injured and 28 U.S. marshals wounded by gunfire.

Another 28 people would face injury the following January when they united to sign a document opposing discrimination, communism and the closing of public schools to establish private academies using state funds. The white Southern Methodist Conference signed the "Born of Conviction" statement, which was published in The Methodist Advocate.

"I used the statement in some classes to talk about Christian ethical dilemmas, particularly related to race," said Reiff, who was a 10th-grader at Murrah High when schools desegregated and is now an associate professor of religion at Emory & Henry College in Virginia. He is writing a book about the Born of Conviction signers, 17 of whom are still living.

"To put it mildly, all hell broke loose," said Inman Moore, pastor of Leggett Memorial Methodist Church in Biloxi and founding member of the Mississippi Council on Human Relations, remembering when he signed the statement. "It was like an atomic bomb in Mississippi. Our statement was a very moving document. It moved most of us right out of the state."

Moore said within six months of the document's publication, 20 of the 28 signers had left Mississippi for Florida, Indiana, New Jersey, Iowa, Texas, Arizona, Colorado and Washington. Thirteen went to California.

"Because there were so many of us coming at one time, California Methodists dubbed us 'The Mississippi Mafia,'" he said.

Jerry Trigg was pastor of Caswell Springs Methodist Church in Pascagoula when he helped write the statement.

"There were clergy throughout the state who were having tires slashed and crosses burned," said Trigg, who learned that the Alabama Ku Klux Klan planned to kill him and dump his body in a river. They had been infiltrated by the FBI, who informed the town sheriff - Trigg's good friend and a church member. Community members took turns sitting on Trigg's porch to make sure he was safe.

Trigg went on to lead the 4,000-member First Methodist Church of Colorado Springs, the third-largest church in the West.

The experience in Mississippi, he said, taught him "certain challenges are very difficult, but it by no means diminishes their importance. The key thing is to try to understand what God desires and act upon it no matter how tough it is."

Summer Walters was 27 and working at Jefferson Street Methodist Church in downtown Natchez when he signed the statement.

After it was published in The Methodist Advocate, Walters received a call from city leaders asking him to meet them. They forced him out of town, but he luckily landed a job in Indiana.

"That was like having a fresh supply of oxygen when you think you are choking to death," he said. "It was just really a gift from God. We had a place to live, a parsonage, a guaranteed minimum salary and a chance to start a new ministry - out of Mississippi."

Walters worked for various Indiana churches over the years. "Profound systematic change doesn't happen dramatically without revolution," Walters said. "If you don't do what you think is the right thing, what is your life about?"

Maxie Dunnam grew up in rural Perry County and helped found Trinity Methodist Church in Gulfport, but he was forced to leave after signing the statement. The journey took him to California, then back down South, where he became the world editor of The Upper Room, a Methodist devotional. He also served as president of the Kentucky- and Florida-based campuses of Ausbury Theological Seminary, and the Florida Dunnam campus in Orlando bears his name.

Dunnam never regretted signing the statement, but said he has wondered what might have happened if he'd stayed.

"I doubt my path would have been the same at all, and you have to rest in the fact that God uses us whether we've made a mistake or not in terms of staying or leaving," he said.

"I doubt that I would have been exposed to the world and had a world ministry if I had stayed there simply because of the nature of the church in that particular time in history. I think the biggest thing I learned is the Gospel is always counter-cultural. It does not affirm the status quo."

Unlike these ministers, Denson Napier, who was working in Perry County at Richton Methodist Church when he signed the statement, said he never faced negative repercussions. He received community support.

"If you have people who are committing themselves to the Christian way of living and to truth, they are making sure their power is used to be helpful not hurtful," he said.

But Joe Way, who was 29 and working at a Meridian church when he signed the statement, was forced out of the Methodist conference.

"Once I realized there was no way in the world I was going to get a church in Mississippi, I decided to become an Air Force chaplain," he said.

Way served 23 years in the military before returning to Mississippi to become a pastor near Pascagoula.

"It was just something that had to be done because of what I believed," he said, recalling the statement.

Reiff said there were many things that were much more pivotal than the Born of Conviction statement in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, but it was a notable step.

"I think a lot of white Mississippians could fairly easily dismiss the Civil Rights Movement folks as outside agitators or crazy," he said, "but it was much less easy to dismiss ministers of the white Methodist churches who had grown up in Mississippi, who were leaders of their communities."

What is the legacy of the 28 and the Born of Conviction statement today?

"I think it teaches that people need to speak their convictions," Reiff said, "particularly in situations where there is injustice, and the injustice seems to be supported by the majority of people."