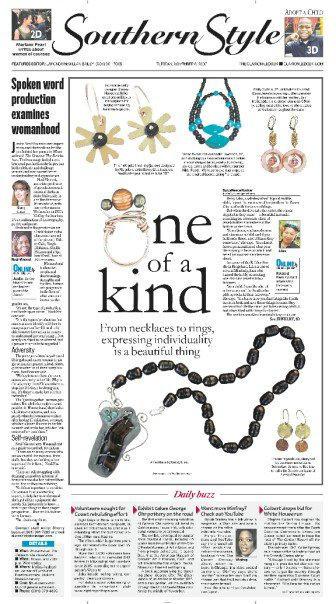

One of a kind: From necklaces and rings, expressing individuality is a beautiful thing

LaReeca Rucker

The Oxford Eagle

Betsy Liles, a self-described "typical middle child," spent the summers of her youth in the Yazoo City pool with her seven siblings.

But when she dove into the water, she was as atypical as they come - a beautiful mermaid searching for a treasure chest of jewels hidden somewhere at the bottom of the ocean.

"Sometimes, you have dreams and visions as a child, and if you hold onto those, a lot of times they come true," she says. "You almost have a premonition of what your life is going to be as an adult, and here I am now with my treasure chest."

As owner of the B. Liles Studio in Ridgeland, Liles is one of several Mississippians who turned the hobby of creating one-of-a-kind jewelry into a business.

"As a child, I was like a lot of other women of the South who pick up rocks in their driveway," she says. "You know how you find things like fossils on creek beds and save those things because they are beautiful? By the time I got to be a young adult, I had a box filled with things I collected."

Her work is sometimes contradictory - a contrast of classic and rustic that she believes symbolizes the Southern woman. "You have women who are comfortable digging in the dirt," she explains, "but when the time calls for it, they will put on their pearls and dresses."

One-of-a-kind jewelry is a trend sought by today's women who are seeking ways to express individualism, Liles says. "In today's market, you can go anywhere and find a knock-off of anything," she says. "But you see people making their own clothes these days because they don't want to wear the same thing everyone else is wearing."

Laura Schmelzer James is one of those people. As a child, if a necklace didn't suit her, she'd get her daddy's pliers, disassemble the baubles and create a new piece of jewelry from scratch.

"I was always obsessed with my mom's and grandmother's old vintage jewelry," says the Jackson Academy graduate who is gaining recognition for her new eco-friendly jewelry line.

James, 31, uses recycled materials when handcrafting earrings, necklaces and bracelets, and some will be featured in Lucky Magazine's December gift guide and Lucky Breaks section.

The daughter of Jackson residents Joe and Gwen Schmelzer was taught fearlessness, a quality that helped her convince business owners to sell her jewelry in 40 stores in seven states.

"My dad had me doing fear-defying activities when I was younger," she says. "We went paragliding off a cliff in Wyoming. When I was 16, we went scuba diving with sharks in Belize, and we went white water rafting in a classified area on the Salmon River in Idaho.

"Any artist will tell you it's extremely hard to put yourself out there, and I think that helped. My father always wanted me to face my fears."

Like Liles, much of James' jewelry is Mississippi-inspired. Other collections were created after travels to California, New York and Japan. The Charlotte resident graduated from Ole Miss with a degree in fashion merchandising, a major that allowed her to spend time in Europe learning the industry's history.

Jackson jewelry designer Stacey Hansen, another Mississippian who turned a jewelry-making hobby into a business, says people want something that sets them apart from others.

"We are inundated with mass-produced items everywhere we go," she says, "and I think people are really getting tired of it."

The 26-year-old founder of Wildflower Designs graduated from Mississippi State University with a degree in psychology. In 2001, a college professor taught her the art of jewelry-making.

"I learned some simple wire-wrapping techniques with semi-precious gemstones," she says. "Since then, I've continued with metal work. I got a torch last year for Christmas, and I have been soldering things and playing with torch-fired enamel."

Hansen promotes her jewelry on MySpace and the Web site Etsy, a marketplace for buying and selling handmade goods. Rob Kalin, 27, and two other Brooklyn artists founded Etsy in 2005. Since then, the site has grown to 45 employees, 550,000 registered users and 60,000 individual artists selling more than 700,000 handmade creations.

Matthew Stinchcomb, vice president of communications for Etsy, says a "one-of-a-kind" renaissance seems to be occurring.

"I think 100 years ago or 200 years ago, everything was handmade," says Stinchcomb, 32. "And with the industrial revolution, producer and consumer got further and further away from each other.

"We stopped having a connection with people who provided goods. Everything is so disposable now. That makes handmade things more special, and it's only made more profound by the social climate of the world."

When Jackson native LaDonna Spencer, 27, isn't studying law at Southern University Law Center in Baton Rouge, she makes jewelry.

"I give it as gifts to people or wear it myself," Spencer says. "My goal is to one day open a community center and teach young girls to make jewelry."

When in town, Spencer frequents stores like Hancock Fabrics and Village Beads to buy supplies.

Ann Bankston and family members opened Village Beads eight years ago in Ridgeland and immediately realized the popularity of jewelry making. "I couldn't keep enough supplies," she says.

The business is still going strong today, offering classes, parties and even a beading cruise to Cozumel next January.

"It's a hobby that fits our busy lifestyle," Bankston says. "Most people don't have a lot of time to make something, but you can make a beautiful necklace in 15 minutes."

Stinchcomb says the popularity of handmade, unique items may also indicate the changing attitudes of younger generations.

"When I grew up, we didn't have home economics or anything like that in school," he says. "I think that in the 1970s, you had a lot of women rejecting that because it was a role that had been prescribed to them in the 1950s.

"In the 1980s, we were discovering computers and technology, and crafting was considered part of the past and a more unenlightened time.

"I think a lot of people are interested in crafts now for the first time in their lives. Because of the global economy and the huge big box chain stores, the same goods are going to be wherever you go."

Stinchcomb says the world is too homogenous for the younger generation who, thanks to technology, expect customization and personalization to suit their individual tastes.

"We don't want to be told what we're going to wear, and what we're going to do,"he says. "We want things exactly the way we want them."

Where they learned their craft

Members of the Jackson-based Mississippi Gem and Mineral Society taught Betsy Liles, a former nurse, the basics of jewelry-making, but a desire to polish the hobby led her to enroll in North Carolina's Penland School of Crafts. She also took classes at San Francisco's Revere Academy of Jewelry Arts and the Florida Society of Goldsmiths.

"I learned some of the more complicated processes that allow you to really have a voice with your jewelry," said Liles, whose work is greatly influenced by Mississippi.

Laura James studies each summer at the Penland School of Crafts.