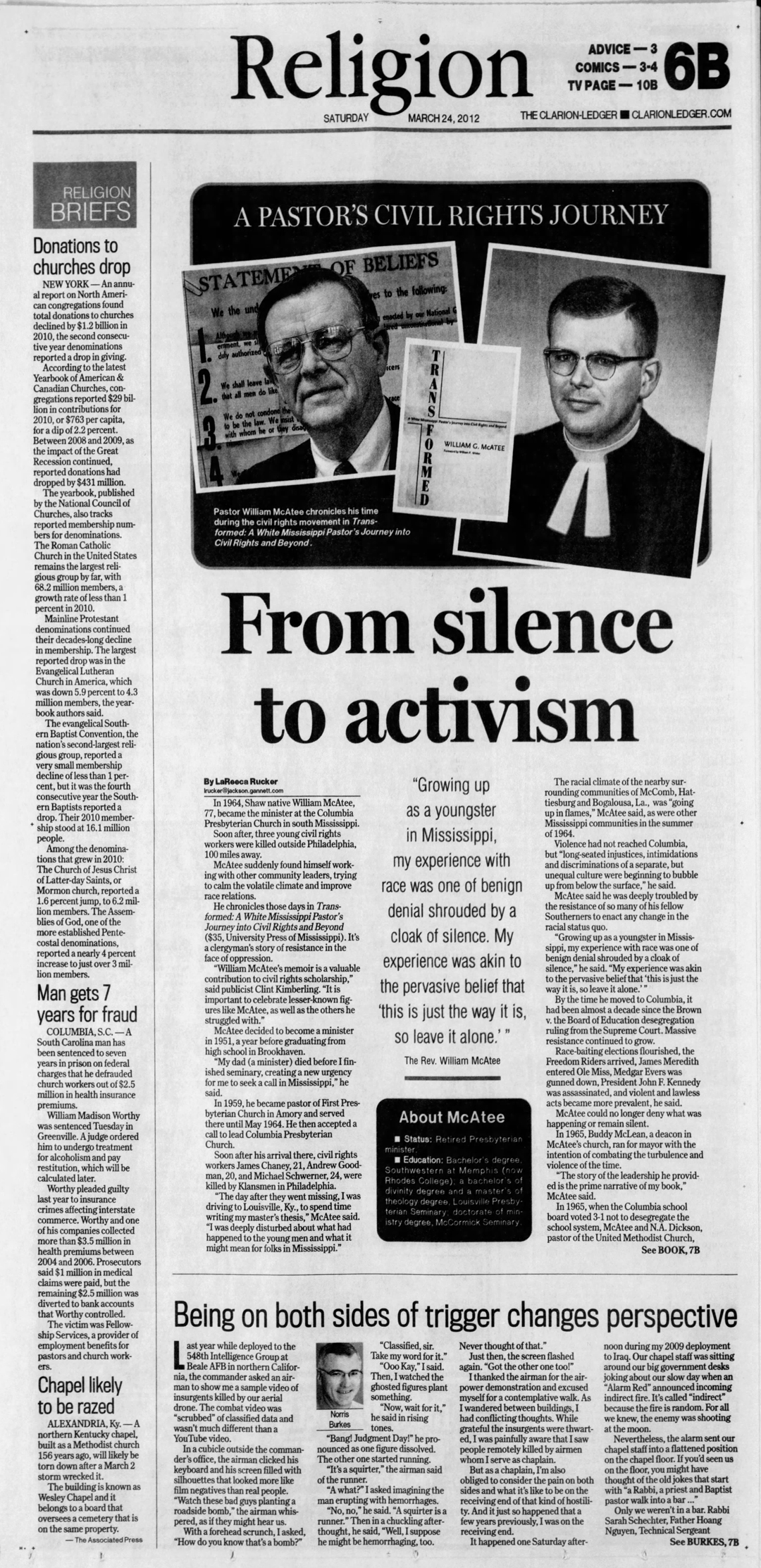

A pastor's civil rights journey: From silence to activism

LaReeca Rucker

The Clarion-Ledger

In 1964, Shaw native William McAtee, 77, became the minister at the Columbia Presbyterian Church in south Mississippi. Soon after, three young civil rights workers were killed outside Philadelphia 100 miles away.

McAtee suddenly found himself working with other community leaders, trying to calm the volatile climate and improve race relations.

He chronicles those days in Transformed: A White Mississippi Pastor's Journey into Civil Rights and Beyond ($35, University Press of Mississippi). It's a clergyman's story of resistance in the face of oppression.

"William McAtee's memoir is a valuable contribution to civil rights scholarship," said publicist Clint Kimberling. "It is important to celebrate lesser-known figures like McAtee, as well as the others he struggled with."

McAtee decided to become a minister in 1951, a year before graduating from high school in Brookhaven. "My dad (a minister) died before I finished seminary, creating a new urgency for me to seek a call in Mississippi," he said.

In 1959, he became pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Amory and served there until May 1964. He then accepted a call to lead Columbia Presbyterian Church.

Soon after his arrival there, civil rights workers James Chaney, 21, Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, were killed by Klansmen in Philadelphia.

"The day after they went missing, I was driving to Louisville, Ky., to spend time writing my master's thesis," McAtee said. "I was deeply disturbed about what had happened to the young men and what it might mean for folks in Mississippi."

The racial climate of the nearby surrounding communities of McComb, Hattiesburg and Bogalousa, Louisiana, was "going up in flames," McAtee said, as were other Mississippi communities in the summer of 1964.

Violence had not reached Columbia, but "long-seated injustices, intimidations and discriminations of a separate, but unequal culture were beginning to bubble up from below the surface," he said.

McAtee said he was deeply troubled by the resistance of so many of his fellow Southerners to enact any change in the racial status quo.

"Growing up as a youngster in Mississippi, my experience with race was one of benign denial shrouded by a cloak of silence," he said. "My experience was akin to the pervasive belief that 'this is just the way it is, so leave it alone.'"

By the time he moved to Columbia, it had been almost a decade since the Brown v. the Board of Education desegregation ruling from the Supreme Court.

Massive resistance continued to grow. Race-baiting elections flourished, the Freedom Riders arrived, James Meredith entered Ole Miss, Medgar Evers was gunned down, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and violent and lawless acts became more prevalent, he said.

McAtee could no longer deny what was happening or remain silent.

In 1965, Buddy McLean, a deacon in McAtee's church, ran for mayor with the intention of combating the turbulence and violence of the time.

"The story of the leadership he provided is the prime narrative of my book," McAtee said.

In 1965, when the Columbia school board voted 3-1 not to desegregate the school system, McAtee and N.A. Dickson, pastor of the United Methodist Church, challenged the business leaders of the community.

"We took this step as a way to be supportive of the mayor in his leadership, McAtee said. "We also decided to make contact with fellow black clergy to build bridges in the community. Their initiatives later helped the mayor influence the community to peacefully comply with the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

"I was a minor player in bringing about change in the community," he said, "but nonetheless I had a front row seat to what was transpiring."

Serving as a pastor in Mississippi at this time proved to be a life-changing experience.

"My brief pastorate and community involvement in Columbia became my 'defining moment' when I came to terms with putting my faith into practice," he said. "... I discovered I could speak quietly and take a stand that made a difference."

He left Columbia in 1966 to work in Richmond, Virginia., with the Presbyterian Church's Board of Christian Education. In 1971, he moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he still lives since retiring in 1997.

"Looking back, I see how my views on race were evolving, how I was constantly challenged to overlook deep-seated predjudices as I began to know blacks from who I had been separated by a debilitating social system not always of my own doings," he said.

"I also learned that, even though I was being transformed in my experience with race relations in concrete ways during those short years, I still am a work in progress."

McAtee learned a few lessons he now teaches others.

"It is hard to be proud of family lineage and cultural heritage, yet not recognize the evil that at times lurks within them," he said. "Repentance is an important landmark on the way to reconciliation and forgiveness."

Corinth resident Frank Brooks, a retired minister who became friends with McAtee in 1956 when they entered seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, said McAtee's book is an excellent blend of his friend's own feelings about race and his hard work in Columbia "to try to integrate the schools and facilities there with gentleness, understanding and peace."

"The book is a challenge for us to be more loving and accepting persons of all people."